Victorian Wallingford’s ‘Red Light’ District?

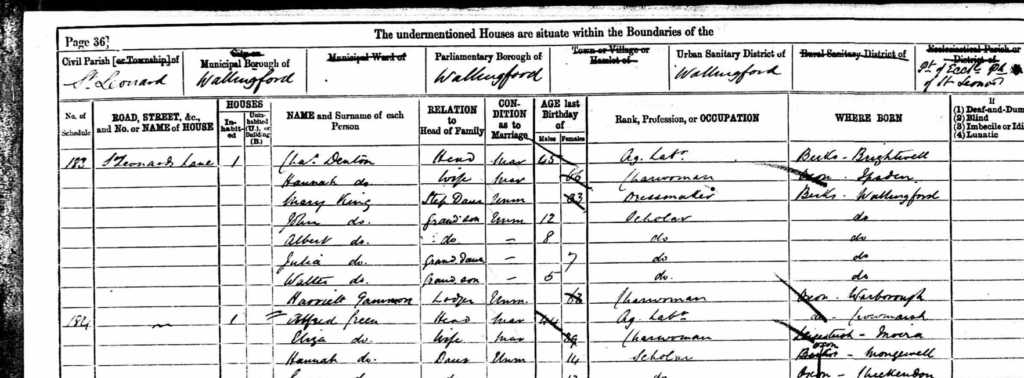

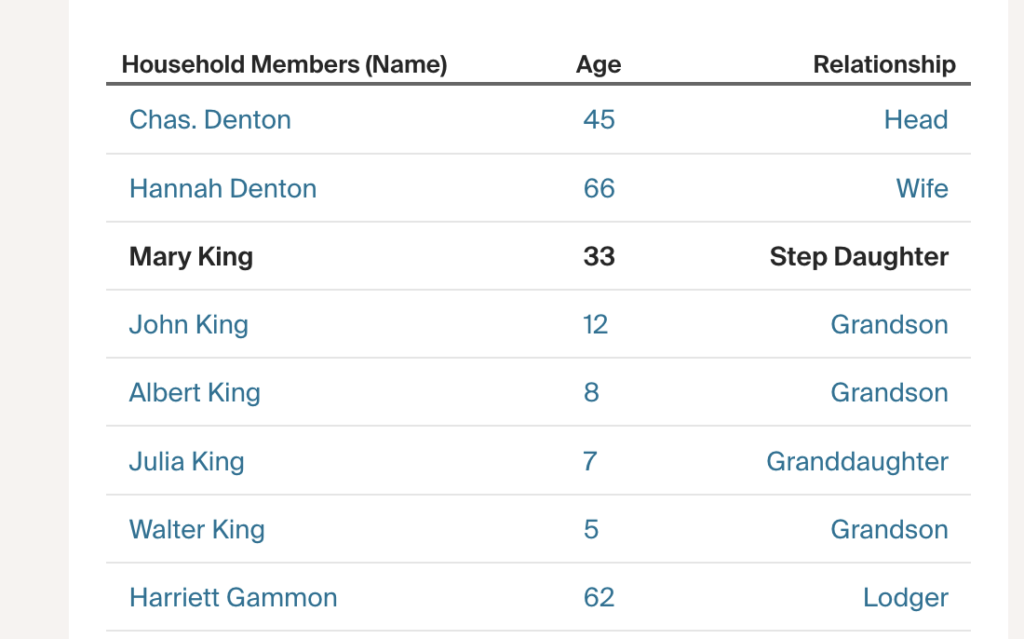

It’s the 4th April 1881. Charles Allnatt, a Post Office clerk, is knocking on doors in St Leonard’s Lane, Wallingford. He’s the local census enumerator and he’s collecting information from residents about who was living in each house at midnight on the previous night – national census night.

In one home he finds that Mary King, a 35 year old single woman who never married, is living with her mother, Hannah, and stepfather, Charles Denton. There are also 4 grandchildren: Albert (14), John (12), Julia (7) and, the baby of the family, Walter who is just 3 years old. All of the grandchildren have the family name King and there is no record of their father or fathers.

When Charles Allnatt calls at the same house 10 years later for the 1891 census, there is no mention of Mary. Her mother and stepfather are still living there. They’re looking after Walter, now a teenager, and another granddaughter, Octavia King (8). The other children have probably grown up and moved away.

Sadly, it seems likely that Mary King and a sixth child, Charles, had both died during childbirth in 1887.

Why was an unmarried woman living with her mother, stepfather and 5 apparently fatherless children in this particular area of Victorian Wallingford?

At the end of the nineteenth century St Leonard’s Lane and Lower Wharf would have been very different to the quiet area it is today. Then, there would have been a shifting population of labourers and watermen associated with the busy river traffic on the Thames. Where labouring men work away from home, they often spend their money on the same three things: gambling, alcohol and sex.

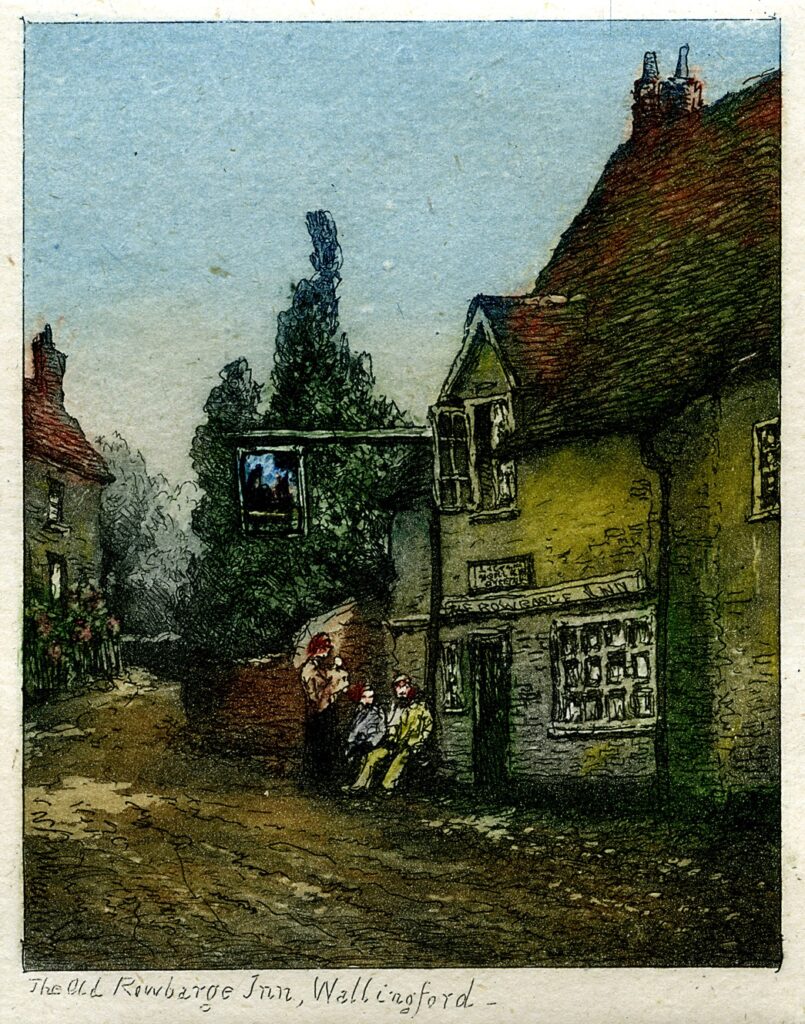

There are records about local lodging houses and pubs for drinking and gambling. The Row Barge was at the river end of St Leonard’s Lane and the Anchor was just a few yards away on the other side of the street. Not surprisingly, the police were kept busy dealing with drunkenness and fighting.

However, prostitution is generally hidden.

Single women living in lodging houses were sometimes described as ‘unfortunates’, but often women sex workers showed themselves as ‘dressmakers’. The social calendar of affluent people in Victorian times meant dressmaking was a seasonal occupation for many seamstresses. Sex work provided a living when no-one was ordering new finery for balls, soirees and other glamourous events.

The 1891 census shows that, compared to other areas of Wallingford, St Leonard’s parish had a higher proportion of women who gave birth in their 40s, unmarried women in their 20s described as unemployed or dressmakers and married women living with their parents whose husbands were ‘absent’.

The fact that Mary King lived with her mother and stepfather and had 6 illegitimate children doesn’t necessarily mean she was a sex worker. There are other possible explanations for her story. Perhaps her stepfather Charles Denton was the father of some or all of her children?

But it seems likely that Mary made her living through sex work in what may have been Victorian Wallingford’s riverside ‘red light’ district. GE